What are the differences between Airbus and Boeing?

What are the differences between Airbus and Boeing?

The main difference between Airbus and Boeing have historically been their design philosophy. This really comes down to differences in how the aircraft are operated by the pilots, something which goes unnoticed by the passengers.

There are now many different models of Airbus and Boeing aircraft ranging from old to new, and very big like the B747 Jumbo Jet or A380, or much smaller like the A319 or B737. The best way to describe the fundamental differences of Boeing and Airbus is to compare it’s two short haul aircraft, the A320 and B737.

Airbus A320 vs Boeing B737 Differences

The A320 and B737 are the most widely used short haul aircraft by airlines around the world by some margin. As a passenger you might notice a few subtle differences between these two aircraft, both inside and out.

Airbus vs Boeing – Interior

Cabin Width

The A320 is a bit wider than the B737 (by about 7 inches) so you will notice the cabin isle is a bit wider. Whilst the seat specifications are decided by individual airlines, the A320 passenger seats are generally a fraction wider.

Leg Room

Leg room, or the space between the seats, is decided by the airline not the manufacture. So, if you find yourself on a 4-hour flight getting sore knees from the seat in front, blame the airline not Mr Boeing or Airbus!

Fuselage Curve

Because the fuselage of the B737 is a bit narrower than the A320, it has a more aggressive curve to the front of the fuselage. Therefore, if you are sat towards the front of the aircraft, you might notice you have a bit less head and shoulder room if you are sat in a window seat up against the fuselage.

Windows

The passenger windows on the B737 are slightly larger than the A320. However, they are also slightly lower which might mean you are finding yourself leaning down to look anywhere but down!

Inflight Entertainment (IFE)

This is the same principle as leg room, it’s decided on by the airline and not the manufacture. Buying a plane is a bit like buying a new car in that you can choose from optional extras to be added. One of these optional extras is whether to include Inflight Entertainment or not.

Noises

When flying on the A320 and the aircraft initially pushes back to start the engines, the pilots pressurise the hydraulics through the ‘Power Transfer Unit’ or PTU. This makes a type of ‘squelching’ noise under the floor around the middle of the cabin, where the undercarriage is located.

On the A320, just after take-off, you will usually hear a single chime. This chime indicates to the Cabin Crew that the landing gear has been retracted.

Airbus vs Boeing Exterior

The best ways to spot the difference between an A320 and a B737 is by looking at the nose, engines and wing tips.

Nose

The A320 has a much more rounded nose which isn’t very long. The nose on the B737 is somewhat longer making it look a bit sleeker.

Engines

The A320 engines look larger and are symmetrically rounded when viewed from the front. The B737 engines appear a bit smaller and have a ‘flatter’ spot on the bottom of the engines when looking at them head on. This is because the B737 sits lower to the ground than the taller A320, meaning it’s engines are also closer to the ground. This flat area on the bottom of the engine helps to protect against a ‘pod strike’ where the engines could make contact with the ground on take-off or landing due to inadvertent roll.

Wingtips

Both Airbus and Boeing use wingtip devices which reduce drag and increase fuel efficiency. The B737NG and older Airbus’s are easy to tell apart as one uses wing fences and the other uses winglets. However, both also use Winglets (Boeing) and Sharklets (Airbus) which look very similar and are difficult to tell apart.

The Differences Between the Airbus and Boeing Flight Decks

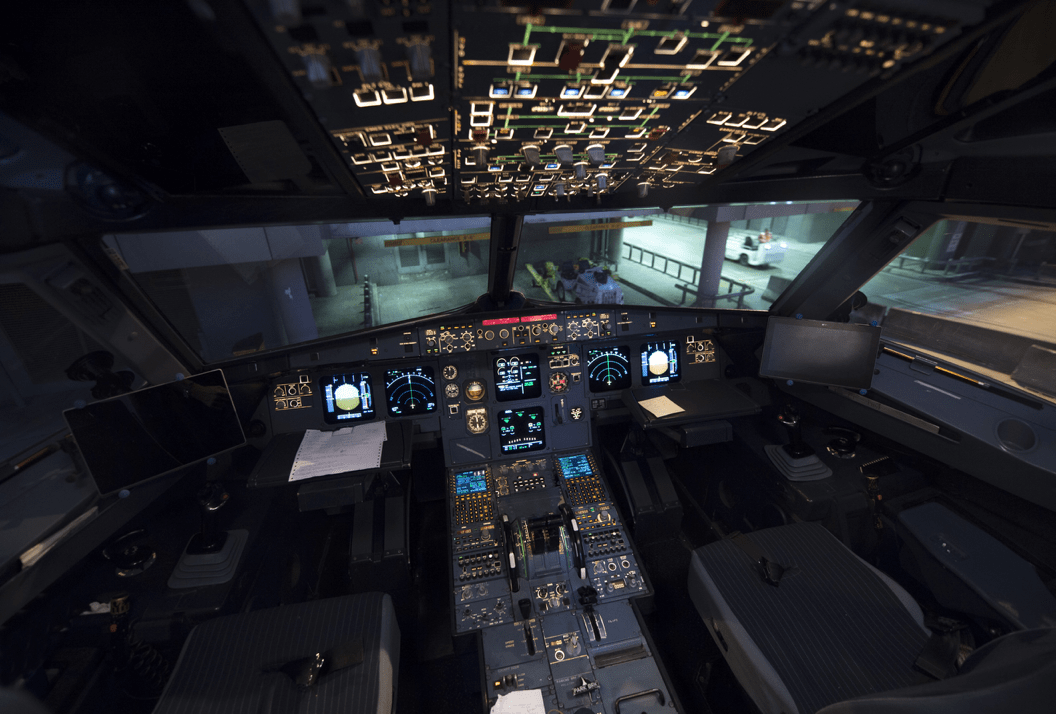

From looking into the flight deck, you can see there are a couple of obvious differences. The Airbus 320 flight deck is larger, both in width and length and feels much more spacious.

In front of the pilot seats, the Boeing has a large control yolk which the pilots use to steer the aircraft whilst the Airbus has a sidestick located to the outer side of each pilot. Instead of a large control yolk, Airbus simply has a retractable tray table which the pilots are able to use for their paperwork.

On the Boeing when the auto thrust is engaged, the thrust levers move as aircraft trust requirements change. However, on the airbus, the thrust levers don’t move with auto thrust engaged.

A320 Flight Deck

B737 Flight Deck

Airbus vs Boeing – Under the Bonnet

The biggest difference between Airbus and Boeing goes on behind the scenes and is related to the automation philosophy of the aircraft. We have published a more in-depth article on this here but on this page, we will provide a basic summary.

In essence, the Airbus places the autopilot and hard limitations at the centre of its design. The Airbus provides full flight envelope protection in that it will not allow the pilots to exceed certain parameters. These are called ‘hard limits’. Examples include stopping the pilots from stalling the aircraft or exceeding certain pitch or roll parameters.

Boeing place the pilots at the centre of its design philosophy and ensure that the pilot have full control authority at all times. This means that at any point, they can simply disconnect the autopilot and fly any manoeuvre required at any given time.

Both philosophies have benefits and drawbacks. Human error is almost always present in aviation accidents so some people argue that the Airbus hard limits help prevent inadvertent human error. However, this requires complex systems which can go wrong and aren’t always understood properly. This can (and has) also led to aviation accidents.

Fly-By-Wire vs Conventional Controls

Whilst more modern Boeing aircraft such as the B787 ‘Dreamliner’ use fly-by-wire technology, the big difference between the A320 and B737 is that the A320 uses fly-by-wire whilst the B737 uses conventional mechanical controls. The traditional mechanical controls of the B737 mean that there is a direct connection through cables and pulleys (hydraulically assisted) from the control column to the aircraft’s flight controls. This means that the pilots are directly manipulating the aircrafts flight controls to manoeuvre the aircraft.

The fly-by-wire system used on the A320 means that when the pilot makes an input into the Sidestick, the input is turned into an electrical signal. This electrical signal passes through a flight control computer which then provides an appropriate output to the flight controls, i.e. the pilots are not directly controlling the aircraft rather a computer is constantly working out what the pilots are trying to do, judges if it is safe and then provides an appropriate control output.

The advantages of Fly-by-wire is that it is much lighter as not large, heavy metal cables are required and therefore provides greater fuel efficiency. It also means that the computers can stop the pilots doing anything which it believes is inappropriate for the stage of flight. However, the fly-by-wire system is complex and can go wrong or misinterpret the situation although there are redundancies and mitigations in place should this occur.

Which is Safer – Airbus or Boeing?

Both the A320 and B737 are extremely safe aircraft. The Boeing 737 has an accident rate of approximately 1 in 16 million flight hours whilst the A320 is very slightly lower at 1 in 14 million flight hours. To put it in perspective, you are far more likely to be involved in a car crash than a plane crash. PBS report that your chances of being killed in a plane crash are 1 in 11 million compared to a 1 in 5,000 chance of being killed in a car crash.

Which is better from a pilot’s perspective – Airbus or Boeing?

From a pilot’s perspective, there have been debates for decades over which is the ‘better’ aircraft. The reality is that both Airbus and Boeing have their advantages and disadvantages and deciding on which one is better is very much down to personal opinion. Some pilots prefer the spaciousness and tray table of the Airbus whilst others prefer the design philosophy of the Boeing knowing that they can disconnect the aircraft and fly it manually without restriction at any point should they need to.

Which is better from a passenger’s perspective – Airbus or Boeing?

From a passenger experience point of view, there isn’t a huge difference between the two aircraft. On the A320, the seats might be a bit wider but ultimately the leg room and inflight experience delivered by the cabin crew is much more likely to influence your opinion on which is better, not who made the aircraft.

Different Models

The A320 and B737 are actually families of aircraft and there are certain types of both aircraft. The differences in the models generally represent size and range. The larger the designator (i.e. an A321) the bigger the aircraft is both in terms of size and weight, the more passengers it can carry, the more powerful its engines and the further it can fly. Other performance factors such as maximum speed and altitude are generally about the same.

The A320 family consists of:

- A318

- A319

- A320

- A321

Airbus have recently updated the design of their A320 family aircraft and the new models of the A320 families include:

- A319neo

- A320neo

- A321eno

There are also Long Range and Extra Long-Range versions of the A321 named:

- A321LR

- A321XLR

The Boeing family of aircraft consist of the Boeing 737 Original, B737 Classic, the updated B737 Next Generation (NG) and the brand new B737 MAX.

B737 Original

- B737-100

- B737-200

B737 Classic

- B737-300

- B737-400

- B737-500

B737NG

- B737-600

- B737-700

- B737-800

- B737-900

B737 MAX

- B737 MAX-7

- B737 MAX-8

- B737 MAX-9

How Much Does a B747 Jumbo Jet Weigh?

How Much Does a Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet Weigh?

The maximum weight of a Boeing 747-400 Jumbo Jet is 910,000 lbs or 412,000 KGS. This is equivalent of 35 double decker buses! It would reach this weight when it is full of passengers and has a lot of fuel onboard.

The weight of an empty Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet without any passengers, freight or fuel is 412,300 lbs or 187,000 KGS. To put it in perspective, this is more than 4 times heavier than the empty weight of a Boeing 737-800 (which is 91,300 lb / 41,413 kg).

The maximum fuel capacity of the B747 is about 230,000 litres, which is about 184,000 KGS. If the Jumbo is carrying a full fuel load and this is added to the empty operating weight of the aircraft, it leaves about 41,000 KGS of weight for passenger and freight.

Virgin Atlantic Boeing 747-400 Jumbo Jet

Maximum Cargo Weight of the B747 Jumbo

The special cargo version of the B747-8F Jumbo Jet can carry up to 134,000 KGS of cargo. This is the equivalent of about 78 BMW 3 Series cars, so it’s certainly a lot! However, the cargo space is limited to 856m3

Did you find this article interesting? You might be interested in: How much does jet fuel cost?

What’s the Longest Passenger Flight?

What is the World’s Longest Passenger Flight?

As of 2021, the World’s longest commercial passenger flight is a Singapore Airlines service from New York (Newark) to Singapore at a distance of 9,540 miles and taking anywhere from between 17 :30 to 19 hours. The route is flown by the state-of-the-art A350 aircraft.

In second place is a Qatar Airways B787 service from Doha, Qatar to Auckland, New Zealand at a distance of 14,536 km, taking in excess of 17 hours.

This is very closely followed by a Qantas Boeing 787 service from Perth in Australia to London in the United Kingdom at a distance of 14,498 km with a flight time of over 17 hours.

Other noteworthy routes include:

An Emirates A380 service from Dubai to Auckland, consisting of 14,200 km with a flight time of 17 hours 15 minutes.

Dallas Fort Worth (United States) to Sydney, Australia with a total distance of 8,568 miles or 13,790 kilometres. This is operated by Qantas on their Airbus 380 aircraft.

Delta Airlines Boeing 777-200LR from Atlanta (United States) to Johannesburg (South Africa). This consists of a distance of 13,572 kilometres or 8,433 miles.

If you found this article of interest, check out our page on ‘How Much Fuel Does a Jumbo Jet Burn?‘

Why Can’t You Vape on a Plane?

Why can’t you vape on a plane?

The reasons why you can’t vape on a plane include the vapour being mistaken for smoke, the potential fire risk from a malfunction and the fact it is classed as anti-social.

Vaping on a passenger jet – an introduction

As with smoking, commercial airlines won’t allow you to vape e-cigarettes on flights. Many wonder why they are banned as you might think they pose much less of a fire risk than from a regular cigarette and the vapour dissipates much quicker than smoke. Well there’s a few good reasons why they are banned.

Hold Luggage & Fire Risk

If items of luggage apply pressure to an e-cigarette, it can be activated unintentionally. If it’s continually activated, it can cause the battery to overheat which might result in a fire. As the luggage in the hold is unattended, in the past this has caused in-flight fires.

The Sight of ‘Smoke’

One of the worst situations that can develop in an aircraft is an inflight fire. Cabin Crew are therefore trained to be constantly on guard for sources of smoke. With someone sat down vaping behind a seat, it would be very difficult for the Cabin Crew to tell the difference between real smoke the vapour from an e-cigarette. With a few passengers vaping, a genuine source of smoke might go unnoticed for a prolonged period which could develop into a fire.

Smoke Detectors

Most aircraft smoke detectors can’t differentiate between vapour and smoke. If you vape in the toilets, the smoke detector will go off. This raises in alarm in the flight deck and has to be investigated by the Cabin Crew.

Second Hand Smoke

With fewer and fewer smokers in the population, second hand ‘smoke’ has become increasingly socially unacceptable, as has second hand vapour from e-cigarettes. Given the reducing number of smokers and vapers, it’s reasonable to assume that the vast majority of passengers are quite happy with the airlines decision to ban vaping on flights. Whilst its banned, it’s also just common courtesy not to vape in confined spaces.

If you’ve found this article of interest, check out our page on why there are still No Smoking signs on passenger planes.

Why are there Still ‘No Smoking’ Signs on Planes?

Why are there Still No Smoking Signs on Planes?

There are a number of reasons for still having no smoking signs on passenger aircraft. These include the fact it is a legal requirement, it deters people from lighting up and there are still millions of people travelling by air for the first time every year that aren’t always aware of the smoking restrictions.

Smoking on Commercial Passengers Jets

With smoking on planes having been banned for a long time, it’s quite reasonable to ask why there are still no smoking signs and ashtrays on planes. It’s not necessarily obvious, but there are a number of reasons as to why they are still there. These include the following reasons:

Older Aircraft

Up until fairly recently, European and US aircraft were mandated to have an illuminated ‘no smoking’ sign visible to all passengers. The life span of commercial aircraft can extend over twenty years so even though some newer planes have had their no smoking sign replaced with ‘turn off electronic devices’, the vast majority of aircraft still have a no smoking sign installed. However, even when not mandated, most new commercial aircraft are still fitted with a no smoking sign for the reasons below.

Fire Risk

One of the worst emergencies that can occur on a passenger jet is a fire in the cabin and smoking can be serious fire threat. Simply having a no smoking sign visible to everyone can be enough to stop a passenger lighting up.

New Travellers

Whilst you might be a regular traveller, may people across the world still haven’t ever stepped foot on an aircraft or are travelling on a plane for the very first time. The no smoking sign serves as a reminder for those unfamiliar with air travel that you can’t smoke onboard.

Culture

In some cultures, smoking in confined spaces is much more widespread and socially acceptable than others. An aircraft could theoretically be required to operate to any country in the world and therefore a reminder that smoking onboard an aircraft is prohibited is considered good practice.

VIP / Private Operations

It is permitted to smoke on a jet that is being operated privately, but smoking will be prohibited at certain points during the flight or ground operation (such as if refuelling). As large commercial jets can still be used for VIP and private operations, no smoking signs are required to inform the passenger when they can and can’t smoke.

Why are there still ashtrays on planes?

Aircraft still have ashtrays in the toilets and very old aircraft might even have them in the arm rest of each seat. The FAA (the US aviation regulator) requires ashtrays to be installed in each toilet in case a passenger breaks the rules and lights up a cigarette in the toilet. If they do, having an ashtray provides somewhere which allows the safe disposal of the cigarette rather than putting it in the bin, which is full of combustible materials like paper towels and could potentially start a fire.

EASA (the European regulator) have proposed that ashtrays should no longer be mandatory in the aircraft bathrooms. This is based on the fact that it is now widely known and accepted that smoking on aircraft is not allowed whilst on the other hand, having an ashtray visible might even suggest smoking in the toilet is acceptable.

The Penalties

Smoking on a passenger flight in the Western world is against the law. If caught smoking the passenger can be given a significant fine (up to $25,000 in the USA) and banned from future travel by the airline.

Why do Airlines Dim the Lights for Take-off?

Why are the Cabin Lights Dimmed for Take-off and Landing?

Cabin crew turn down the cabin lights for take-off and landing to allow the passengers eyes to adjust to the darkness just in case an emergency occurs which requires the evacuation of the aircraft. If the passengers eyes are adjusted to the darkness, their night vision will be improved which will help them find a route out of the aircraft in an emergency in darkness.

After the cabin lights have been dimmed, you will have the option to use an overhead light which will give you enough light to keep reading but these lights are of reduced intensity so your eyes can still adjust to the lower light levels.

The reason for the cabin lights being dimmed isn’t the same reason the lights are turned down in the cruise (at high altitude en-route) – this is to let you sleep!

Other Cabin Crew Instructions

The Cabin Crew give all the passengers lots of instructions for take-off and landing, like turning off laptops, removing ear phones and ensuring the tray tables are stowed. They aren’t just being awkward, it’s actually for a very good reason – your safety and wellbeing if something were to go wrong.

Why do passengers have to put their laptops away?

If the aircraft came to an abrupt stop or there was an unexpected significant impact, loose articles could be launched around the cabin. Anything the size of a laptop could cause a very serious injury if it hit someone. Therefore, it’s in everyone’s interests that objects such as laptops are stowed in the seat pocket or overhead locker for take-off and landing.

Some airlines will allow smaller handheld devices to be used during take-off and landing as these are deemed small enough to not pose a significant risk, or, could be help onto in the event of an emergency.

Stowing Tray Tables

Cabin Crew ask you to ensure the tray tables are folded back into the upright position for take-off and landing as in the event of a crash, you could violently be pushed into it which could cause serious injury or death.

Raising the Window Blinds

You need to be able to see outside in the event of an accident to assess which side of the aircraft is safe to evacuate. It’s also to allow the Cabin Crew to be able to look outside and assess where any danger is (such as a fire) and therefore decide which emergency exits should be used.

Removing Your Earphones

Some airlines have stopped insisting on this, but some airlines still enforce it. Basically there may be an occasion where the Pilots or Cabin Crew command an evacuation of the aircraft even though the reason isn’t obvious. For example, a fire in the cargo hold. In this scenario they need you to hear the evacuation instructions immediately and clearly. You don’t want to miss half of it because you’re listening to your favourite band!

Seat in the Upright Position

In the event of needing to adopt the brace position, the seat in front of you needs to have its seat in the upright position to make it as effective as possible. So moving your seat into the upright position is actually for the safety of the person behind you, not for you!

How Clean is Air on a Plane?

Is the Air on an Aeroplane Clean & Safe?

Yes, the air on an aircraft is clean, filtered and perfectly safe to breathe. The entire air within the aeroplane cabin is replaced with fresh air approximately every five minutes. The air that is recycled within the passenger cabin passes through a HEPA filter which filters out almost all viruses (including Covid-19) and removes over 99% of bacteria.

How much of the air is fresh?

It varies from aircraft to aircraft, but at any given time approximately 60% of the air within an aircraft is fresh compared to 40% recirculated / reused air. On many aircraft types, the cockpit and therefore the pilots get 100% fresh air.

What filters the aircraft air?

Most aircraft use High-Efficiency Particle Filters (HEPA) to filter the recirculated air. These are the same filters found in hospitals and kill more than 99% of bacteria and stop particles which can carry viruses.

How air on a plane works…

The outside air temperature at the plane’s cruise altitude (approximately 35,000 feet) is as cold as -65°C / -85°F and is so thin that it doesn’t hold enough oxygen for humans to breathe. Therefore, an air conditioning system is used to provide air to passenger cabin which ensures a breathable and comfortable cabin environment for the passengers and crew.

This pressurised air is regulated by the Environmental Control System and Air Conditioning ‘Packs’. The process of pressurising the aircraft starts with air entering part of the engine. Before some of the air goes through the engine combustion process (where air mixes with fuel and ignites to produce thrust), it is redirected into the aircraft’s ‘bleed’ system. This basically means the air from the first part of the engine is fed into various aircraft systems such as the air conditioning and anti-ice systems. This air has been compressed through the initial stages of the engine, and therefore it needs to be cooled down.

Once the air has been cooled to the correct temperature, this fresh air which has been compressed, is directed to the recirculation bay where it is mixed with air that has already been fed through the cabin. Once the two sources of air are mixed, this mixed air is directed to the aeroplane cabin for passengers to breathe.

Recycling of Air

The air then disappears under the floor towards the cargo hold. Some of the air is again mixed with the fresh air whilst the rest leaves the aircraft via the ‘outflow valve’ which is normally found at the rear of the aircraft. The amount of air entering the aircraft is a fairly steady rate; it is the amount of air which leaves the aircraft by the outflow valve which dictates the pressure of the passenger cabin (typically about 6-8psi). The cabin is typically pressurised to an altitude of 8,000ft (see our article on why planes fly so high).

The key point is that the majority of the air is ‘fresh’ (i.e. hasn’t previously been in the passenger cabin) and is also filtered to remove contaminants prior to being distributed to the passenger cabin.

Am I more likely to get ill from being on an aeroplane?

You are at no more risk of getting sick from being a passenger on an aeroplane than you are at being at any other large gathering such as bar, or cinema.

Being on an aeroplane is the equivalent of being in an enclosed space with lots of people except that the air within an aircraft is heavily filtered unlike most other comparable examples. There is a risk of a disease or virus being passed on, but it’s no more than any other enclosed space and arguably less as the air is effectively filtered.

Think of going to a concert, sporting event or even a busy bar. If you are within close proximity to someone who is ill with contagious disease or virus, you are more likely to catch it. However, if people are wearing appropriate personal protective equipment such as face masks, the distance of travel of any contaminants is significantly reduced.

Another point to consider is that the air on an aircraft is dry with low humidity. This dries out the mucus membranes within your nasal passage and this increases susceptibility to virus transmission. However, again, as the air is filtered, the chances of a virus being present in the first place is low.

So, yes, the risk is higher than if you are sat at home by yourself, but arguably safer than a crowded enclosed space such as the cinema.

Article Details:

This article was written by a current airline pilot who has experience as a Training Captain, Pilot Management, Wide Bodied and Narrow Bodied Aircraft over Long Haul & Short Haul Operations.

Do Pilots Get Cheap Flights?

Do Pilots Get Cheap Flights?

Yes, as a perk of the job most pilots have access to heavily discounted or even free flights. It varies between airlines and across countries but it is generally accepted that pilots and their friends or family get access to cheap flight tickets. This article provides a general guide but there will be subtle differences between airlines.

Discounted Flights & ID90

Many airlines give their pilots access to unlimited travel on what is called an ‘ID90’ basis. ID90 is where the flight ticket price is discounted by 90% but on a standby basis, i.e. they will only get on the flight if there is a spare seat available – if the flight is full they won’t get on. These tickets will see the pilots seated anywhere from First Class to Economy depending on where the spare seats are.

It can be a very useful perk of the job given that it gives you the opportunity to potentially travel to the other side of the world for a fraction of the usual cost (sometimes just £150/$200), but it can be a bit nerve racking if you really need to get home, the flight is full and you’re waiting to see if someone doesn’t turn up so you can have their seat!

Airlines usually have reciprocal staff travel agreements with other airlines. This can mean pilots may have access to cheap tickets across a range of airlines around the world.

Free Flights

As well as ID90 travel, some airlines offer their pilots a number of ‘confirmed tickets’ for free every year. This will usually guarantee a seat on the aircraft and would usually be for a seat in First or Business Class. However, whilst there might not be a fare for the ticket, in some circumstances (such as the UK) you will still be required to pay tax on the ticket.

Such agreements aren’t usually exclusive to pilots. Cabin Crew and other airline workers often have access to similar opportunities but their agreements may be slightly different.

If you found this article of interest, check out our page on how much airline pilots get paid.

Do Pilots Work Hard?

Do Airline Pilots Work Hard?

Over a number of years, certain airline executives, parts of the media and even some members of the UK Parliament have stated on various platforms that “airline pilots only work 17 hours a week” and don’t really work very hard. Any commercial airline pilot will tell you this statement is misleading and ultimately serves to undermine the airline pilot profession. This article seeks to explain why.

The reality is that a full time pilot will work much more than an average of 17 hours a week. The 17 hours figure is just based on flight time, not the time actually spent at work and doesn’t take into account annual leave and other rostered duties.

The background behind pilots working hours

In Europe and across much of the World, Pilots are limited in the number of hours they are allowed to fly for safety reasons. These limits are imposed by the aviation regulator (such as EASA or the FAA) which governs the airlines. This important restriction is in place to protect pilots (and thus ultimately passengers) from fatigue, a physiological state which is known to be detrimental to flight safety. Whilst there are complex definitions for fatigue, it can be simply summarised as extreme tiredness or exhaustion.

Long Haul pilots will regularly be awake and flying throughout the night whilst Short Haul pilots will often be getting up at 4am for several days in a row. In both cases it often results in being awake when the circadian rhythm is at its lowest, something which is known to cause fatigue and potentially long-term health implications. Given that pilots are responsible for the safety of hundreds of people at a time and may need to deal with an emergency situation at any point, it’s vital that pilots are well rested and not overworked, hence the hour restrictions in place.

These limits (in Europe) restrict the pilots to a maximum of 100 flight hours in 28 days and 900 flight hours in 1 year.

The misleading figure of only working 17 hours a week comes from dividing the maximum number of flying hours per year (900) by the number of weeks in a year (52).

A pilot’s flying hours are closely scrutinised, with both the pilot and airline required to keep a log of their hours flown and ensure these limits are not breeched.

Why the average working hours for pilots is misleading…

The inference that airline pilots only work 17 hours a week is derived from a maximum yearly flying hour average. However flying hours are not the same as hours at work.

The pilots flight time commences when the aircraft’s parking brake is released for pushback from the gate and it ends when the aircraft comes to a stop on stand at its destination. It is this time which is restricted by the 900 hours per year.

For example, if an aircraft pushed back from Manchester Airport at 09:00, took off at 09:30 then landed in Chicago at 16:30 and arrived in on stand at 17:00, this would equate to an 8-hour flight time for the pilots, even though the airborne time was only 7 hours.

What isn’t taken into account in the flight time is that the pilots will have arrived for duty typically an hour to an hour and a half before the flight to complete their pre-flight duties and that they will be on duty for at least 30 minutes after the arrival at the gate. The time on the ground for turn arounds (the gap between flights) is also not counted as flight time.

Pilot Flying Hours vs Working Hours Example

Let’s take a typical short haul pilot roster as an example. Say this pilot, called Bob, is about to start a 4-day week of early duties. On the first 2 of the days, Bob is doing a 4-sector day (this mean 4 flights in a day such Stansted – Dublin – Stansted then Stansted – Paris – Stansted). On the other 2 days, Bob is working a 2-sector day (Luton – Alicante – Luton).

Day 1, Bob reports one hour before the flight is scheduled to depart. When Bob lands in Dublin, there is a 30-minute turnaround. When Bob lands back in Stansted, there is a 1 hour turnaround before heading off to Paris and a further 40-minute turnaround in Paris. When he eventually lands back at Stansted on the last flight, he is on duty for a further 30 minutes to complete the post flight paperwork.

In such an example (which is very realistic), Bob has worked 3 hours and 40 minutes more than the actual flight time for the day indicates.

Bob does the same pattern on day 2.

On day 3 Bob has the same pre-flight report and post flight duties time. There is a 45-minute turnaround in Alicante, resulting in a total additional time at work of 2 hours and 15 minutes.

Bob does the same pattern on day 4 as he did on day 3.

In this 4-day working block, Bob has therefore worked 11 hours and 50 minutes on top of the flight time. This quickly turns an average of 17 hours a week into a 28:50 week.

How the average works…

So, you are probably thinking that a 28:50 week does sound too bad? But that’s not the whole story. That initial 17-hour average has been calculated assuming pilots fly every single week of the year and are not rostered any other duties or given any annual leave.

Pilots are typically given around six weeks annual leave (free of flying) a year. But in the remaining 46 weeks of the year, they can’t fly every week due to the annual training they need to complete in both the simulator and classroom. Let’s call this an additional 1 week free from flying. So actually the 900 hours should be averaged over 45 weeks the pilot can work, giving an average figure of 20 flying hours a week.

Add Bob the Short Haul pilot’s typical week of an additional 11 hours 50 minutes at work not flying, we’re now up to about 32 hours a week average (almost double the 17 hours stated by some people).

32 hours a week doesn’t sound a lot…

If you take into account that Bob may regularly be working a 5-day work period where his alarm goes off at 04:00 (am) to be at work for 05:30 every day, or perhaps working until 1am in the morning, limiting the total number of hours Bob can work is essential to ensure he is well rested enough to be responsible for the lives of hundreds of people a day.

Whilst some might suggest a more realistic average of around 32 hours work a week still isn’t a lot when compared to other professions, when you take into account the continuous changes in body clock and disruption to the circadian rhythm as well as time spent away from home, averaging a 32-hour week can feel like a lot.

Why say pilots only work 17 hours a week?

It’s usually said by someone who is looking to downplay the role of a professional pilot in order to put pressure on terms and conditions. It’s then picked up by the media and printed as a fact, without the reference to the whole picture.

Next time you hear that ‘Pilots only work 17 hours a week’, you know the truth.

If you enjoyed reading this article, you’ll probably find our page about a typical pilot roster of interest.

Pilot Uniform Guide: What do the Stripes Mean?

What do the number of stripes on a Pilot’s uniform mean?

The number of stripes on a pilots uniform indicate their rank. Ranks are generally split into the following:

- Training Captain

- Captain

- Senior First Officer

- First Officer

- Second Officer

- Cadet/Trainee

There is no worldwide standardisation of stripes across airlines. Different airlines choose to issue a different number of stripes to their pilots depending on their rank, which also varies on experience levels within the airline. The only standardisation is that there is almost always a Captain and First Officer operating the flight (unless it’s a training flight). The Captain and First Officer are sometimes known as a Pilot and Co-pilot).

Training Captain

A Training Captain has all the responsibilities of a normal Captain, but also trains other pilots (both First Officers and Captains). A pilot who is new to the aircraft type or company will fly with a Training Captain until they reach the required standard to fly with a normal Captain. Training Captains are more senior than normal Captain’s, are generally paid more and are selected for the role after showing continuous above average performance in their own checks and tests.

Despite a Training Captain being more senior than the rank of Captain, they both wear the same number of stripes on their uniform at the vast majority of airlines. A Training Captain therefore wear 4 stripes on there uniform.

Captain

The Captain (sometimes referred to as ‘Pilot’) is ultimately in charge of the aircraft, it’s crew and occupants, unless they are flying with a Training Captain (where the Training Captain would be in charge).

The Captain wear 4 stripes on their uniform.

Senior First Officer

Generally speaking a Senior First Officer is someone who has over approximately 1,500 hours of total flight time. Some airlines may have additional requirements, such as holding a full ATPL or being almost ‘command ready‘ which is an airline’s way of saying they have the ability to be promoted to Captain but are waiting for a position to become available.

Anyone other than the rank of Captain or Training Captain is sometimes referred to as the ‘Co-Pilot’.

A Senior First Officer has 3 stripes on their uniform.

First Officer

The First Officer usually wears 2 or 3 stripes depending on the airline. Some First Officers are automatically issued 3 stripes from their day of joining (typically at Long Haul airlines), whereas some start of with 2 and only get 3 when they are promoted to Senior First Officer.

Second Officer

Some (but not all) airlines use the role of Second Officer. This sometimes means a cruise relief pilot (i.e. not sat at the controls for take-off and landing until their experience levels increase).

The Second Officer would normally have 2 stripes on their uniform.

Cadet/Trainee Pilot

Whilst at flight School, cadet pilots could wear any number of stripes depending on the choosing of that specific flight school. Students will often wear 1 stripe when they hold a Commercial Pilots Licence (CPL) and then 2 stripes once their Instrument Rating (IR) is completed.

Some flight schools even issue 3 stripes to their trainee pilots, although this seems a bit over the top given they have not even operated a commercial aircraft at this point!