Easy Mental Arithmetic for Pilots

Easy Mental Arithmetic for Pilots

When flying an aircraft, whether it’s a Cessna 152 or an A380, pilots need to be able to do fairly basic but quite quick mental arithmetic. Of course, there are occasions where complete accuracy is critical, but the vast majority of the time, you don’t need to be ‘bang on’, but rather work to rough ‘ballpark’ figures. Whether it be calculating required descent rates or speed/distance/time calculations, general rules of thumb can help you make these calculations quickly and reasonably accurately.

These rules of thumb also work very well when completing pilot numerical reasoning aptitude tests as part of airline pilot assessments. Such tests often require you to work quickly, but with a number of multiple-choice answers, you often just need to reach a rough figure rather than an exact one. Quickly being able to calculate a good estimate in test conditions can prove to be invaluable in passing an airline pilot selection process.

Some of the most important rules of thumb involve using the 3 times table, the 1 in 60 rule and being able to divide or multiply by 10. Let’s have a look at some examples:

Distance Required to Descend for Aircraft Calculations

Most aircraft plan to descend at an angle of approximately 3 degrees. To calculate how much distance an aircraft needs to fly to achieve a given reduction in altitude, based on a 3-degree angle of descent, a basic rule of thumb can be used:

Distance Required to Reduce Altitude = Total Altitude to Lose / 1,000 x 3.

For example, if you are at 40,000ft and you need to be at 10,000ft at 30NM before the airfield, you need to lose a total of 30,000ft. Divide 30,000ft by 1,000 (simply take away the last 3 numbers when dividing by 1,000), which gives you 30 and multiply this by 3 gives you 90. It will therefore take you about 90NM to reduce altitude by 30,000ft. If you need to be at 10,000ft by 30NM before the airfield, then add this to the 90NM which gives you a start of descent point of 120NM.

This assumes still air conditions at a constant speed. Whilst it depends on aircraft types, for commercial aircraft, adding an extra mile for every 10kts of airspeed you need to lose is a good ballpark figure. So, in the above example, if you start the descent at 300kts IAS, and need to be at 200kts IAS by the time you reach 10,000ft, you would add 10NM to the distance required to lose the altitude (so 90NM becomes 100NM).

Having a headwind or tailwind also needs to be factored when calculating the distance required to descend. As a rough guide, add 1 NM to the distance required to descend for every 10kts of tailwind and reduce the distance by 1 NM for every 10kts of headwind.

Descent Rate Required to Achieve a 3 Degree Descent Angle when Flying

So, you’ve calculated the distance required to descend to a given altitude using the above method. Using the above example, you will be descending at a 3-degree angle over 90NM. But if you are descending at 3 degrees, what descent rate do you need to achieve? An easy way to calculate this is using this basic formula.

3 Degree Descent Rate = 5 x Ground Speed

For example, if you are flying at a ground speed of 300kts, multiply 300 by 5 and this tells you that you would need to descend at 1,500fpm to achieve a 3-degree descent profile. Some people prefer to multiply the ground speed by 10 then divide by 2. Clearly your ground speed will change with altitude as the True Airspeed and Head/Tailwind changes so you will need to periodically review your rate of descent throughout the manoeuvre.

Descend to an Altitude within a Fixed Time Period

ATC will sometimes require an aircraft to descend to a given altitude within a specific time period. For example, “FDF123 descend to Flight Level 320 to be level within 4 minutes”. In this type of scenario, you need to calculate how many feet per minute you need to descend in order to achieve this restriction. This can be calculated using the following method:

Feet Per Minute Required = Total Altitude to Lose / Number of Minutes

For example, if flight FDF123 is maintaining FL360 (36,000ft) and has been told to descend to FL320 (32,000ft) within 4 minutes, the total altitude required to lose is 4,000ft. 4,000 divided by 4 is 1,000, so the aircraft needs to descend at 1,000ft per minute to meet the restriction.

In such a scenario, you don’t necessarily need to be exact, sometimes you can simplify and be conservative with your calculations since the request is usually ‘within 4 minutes’ not ‘exactly 4 minutes’. For example, if you are flying at 25,000ft and are told to descent to 17,000ft to be level within 9 minutes, we know the calculation is 8,000 / 9 (which equals 888 fpm). However, we can turn these into round numbers to make the calculations easier, just remember to do it in a conservative way to ensure the restriction can be made. For example, we can hopefully quite quickly work out that if we descended at 1,000 fpm, we would descend 8,000ft in 8 minutes. Yes, we’d be levelling off one minute earlier than the restriction required, but we have achieved ATCs request.

Speed, Distance and Time Calculations for Pilots

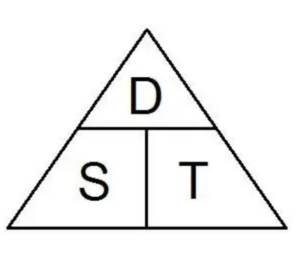

We are probably all aware of the relationship between variables from school and have heard of the Speed, Distance & Time triangle. When flying, we should always be aware of our speed so calculating distance and time is more relevant.

There is a ‘magic triangle’ which can help us quickly remember how to calculate speed, distance, and time. You simply cover up the entity you are trying to find and the reveals how to calculate it. For example, if you cover the ‘S’ you can see that the calculation for speed is distance divided by time.

- Speed = Distance / Time

- Distance = Speed x Time

- Time = Distance / Speed

Easy Speed / Distance / Time Calculations for Pilots

Speed is the distance you travel over a specific time period, so they are intrinsically related. It’s worth understanding some rules of thumb which can help you make quick calculations about distance and time calculations.

- 30kts = 0.5NM per minute

- 60kts = 1NM per minute

- 120kts = 2NM per minute

- 180kts = 3NM per minute

- 240kts = 4NM per minute

- 300kts = 5NM per minute

- 480kts = 8NM per minute

- 540kts = 9NM per minute

- 600kts = 10NM per minute

Remember that there are 60 minutes in an hour. Well therefore, if we divide any speed by 10, this will tell us what distance the aircraft is travelling in 6 minutes at its current speed.

For example, if an aircraft is flying at 150kts, this tells us that it is travelling 15NMs every 6 minutes (150 divided by 10 = 15). Another example is that if the aircraft is travelling at 370kts it is covering 37NM every 6 minutes. You could then halve this number to see how far the aircraft travel in 3 minutes, 1.5 minutes etc.

Put another way, if asked ‘how many miles will you travel in 20 minutes at a speed of 180kts?’. 180 divided by 10 is 18, so 18 miles every 6 minutes. So, if we multiply this number by 3, we know how many miles are covered in 18 minutes (3 x 18 miles = 54NMs). If we cover 18 miles every 6 minutes, we know we cover 9 miles every 3 minutes (it’s then easy to see that it’s actually a mile a minute in this example!). So therefore, we are covering 63 miles every 21 minutes. Knock 3 miles off and we get to 60 NM.

Example Distance to Descend Questions for Pilots

Here’s a few example questions. We’ve got lots more pilot numerical reasoning test example questions over on our dedicated page. The BBC GCSE Bitesize website is also a great resource to help you practice your mental arithmetic.

If an aircraft is flying at an intermediate altitude of 25,000ft and is instructed by ATC to achieve an altitude of 13,000ft by a fix on the arrival, what distance before the fix should the pilots initiate the descent, assuming a planned 3-degree descent profile at a constant speed and still wind?

- A) 40 NM

- B) 38 NM

- C) 36 NM

- D) 28 NM

25,000ft minus 13,000ft = 12,000ft to lose. 12,000 divided by 1000 = 12, multiplied by 3 = 36.

ATC have told you to self-position to a 10NM extended centreline from the landing runway. There are no restrictions other than needing to achieve an altitude of 3,000ft and at a speed of 180kts at the 10NM point. You are currently level at 8,000ft at 250kts and anticipate an average tailwind of 10kts. In order to achieve the restriction, at what point before the 10NM fix should you commence the descent?

- A) 23 NM

- B) 15 NM

- C) 22NM

- D) 16NM

8,000ft – 3,000ft = 5,000ft. 5,000 divided by 1,000 = 5, multiplied by 3 = 15 NM. 250kts – 180kts = 70kts = add on an extra 7NM (1NM per 10kts of airspeed to lose). Add 1NM per knot of tailwind. 15 NM (distance required) + 7 NM (to account for deceleration) + 1 NM (to allow for tailwind) = 23NM.

Example Descent Rate Required Questions

With a 280kts ground speed, what rate of descent do you need to achieve in order to maintain a 3-degree descent angle?

- A) 2,800 fpm

- B) 1,400 fpm

- C) 700 fpm

- D) 2,000 fpm

5 x 280 = 1,400. Or 280 x 10 = 2,800 / 10 = 1,400.

With a 420kts ground speed, what rate of descent do you need to achieve in order to maintain a 3-degree descent angle?

- A) 2,000 fpm

- B) 1,800 fpm

- C) 2,800 fpm

- D) 2,100 fpm

5 x 420 = 2,100 fpm. Or 420 x 10 = 4,200 / 10 = 2,100.

Descend to an Altitude within a Fixed Time Period Questions

If an aircraft is maintaining 27,000ft and has been told by ATC to descend to 13,000ft within 10 minutes, what rate of descent is required?

- A) 1,400 fpm

- B) 1,200 fpm

- C) 1,300 fpm

- D) 1,500 fpm

27,000 – 13,000 = 14,000. 14,000 divided by 10 minutes = 1,400 fpm

If an aircraft is maintaining 35,000ft and has been told by ATC to descend to 30,000ft within 3 minutes, what rate of descent is required to the nearest 100fpm?

- A) 1,600 fpm

- B) 1,700 fpm

- C) 1,500 fpm

- D) 1,800 fpm

35,000 – 30,000 = 5,000 fpm divided by 3 minutes = 1,666 fpm.

TUI Fully Funded Cadet Pilot Programme

TUI Fully Funded Cadet Pilot Programme

TUI UK have launched a fully funded cadet pilot programme. This is an exceptional opportunity to complete your commercial pilot training and going onto join the airline as a First Officer without the huge financial outlay that is usually required. The following information has been taken from the TUI Careers website.

The Program

Embarking upon the 19 month TUI Airline Multi-Crew Pilot Licence (MPL) Cadet Programme is an exciting opportunity for those with little, or no, flying experience. You’ll complete your training and eventually join TUI as a Cadet Pilot flying the Boeing 737. We’re looking for candidates to be committed, resilient and hard-working, and will be rewarded with a dynamic and exciting career where each day is different. Together with your colleagues, you’ll make sure that TUI customers have the best experience whilst travelling to and from their holiday helping them to ‘Live Happy’.

We’re looking for people with great communication and leadership skills, the ability to remain calm under pressure, resilience to work hard throughout a challenging course, motivation to learn and ultimately develop into highly skilled professional pilots.

Eligibility

In order to apply for our MPL Cadet Programme, there are a few requirements that need to be met:

• Be at least 18 years of age on or before 1st September 2023

• Have at least five GCSEs including Maths, English and a Science at grade C/4 or above

• Be fluent in English (verbal and written) with ICAO Level 4

• Be eligible to live and work indefinitely in the UK without additional approvals

• Hold a valid passport which permits unrestricted worldwide travel

• Be at least 1.58cm (5ft 2in) tall

• Able to swim 25m

• Able to obtain a CAA issued Class 1 medical prior to commencing training (at your own cost) – click here for more information

• Before commencing training, complete referencing and pre-employment checks

Funding

The MPL Cadet Programme includes the following:

• All course and training costs

• All training and licence fees

• Accommodation from phase 2 onwards

• Uniform

• ATPL theory exam fees

• All required equipment such as manuals, iPad etc.

Cadets will be liable for:

• Initial Class 1 medical and subsequent renewals

• Personal travel

• Food and personal living expenses

Upon completion of training and joining TUI as a Cadet Pilot, you’ll be paid a Cadet Pilot salary for four years, which will include repayment of training costs to TUI via salary sacrifice. This salary is currently £32,867 (post deduction) and will increase in line with pilot pay scheduling agreements.

Airline Pilot Salary

Updated: October 2022

Disclaimer: The pilot salary figures provided on this page are generalisations and for guidance purposes only. There will always be exceptions both above and below the figures stated.

It should also be noted that over the last two years, thousands of pilots have taken a significant pay cut, or worse, lost their jobs due to the pandemic. Whilst top end pilot salaries can be very lucrative, it can be an extremely volatile industry in terms of job security.

How much do airline pilots earn?

A commercial airline pilot salary can vary considerably between airlines, region and experience. At some of the ‘major’ airlines or Flag Carriers like Emirates, Delta, United Airlines or Qantas, Long Haul Captains may receive a salary of up to $350,000 (USD) / £200,000 a year. The First Officers (or co-pilots) at these major airlines can earn a salary of up to $170,000 / £120,000 a year.

However, junior First Officers who are just starting out in their career might only get paid $25,000 (£20,000) a year. Less experienced Captains or those working at some low cost or regional airlines may start on about £60,000 a year.

In general, the more experience the pilot has and the bigger the aircraft they fly, the higher the pilot’s salary will be. Long Haul pilots are typically paid more than short haul pilots and Captains are paid more than First Officers. First Officers are often referred to as co-pilots.

Pay can also be affected by the amount of variable pay achieved (based on the amount of flying you do and allowances you receive), the amount overtime accepted (which can be very lucrative) and the bonuses on offer.

How much do pilots in the USA get paid?

In the United States, the large ‘major’ airlines pay their pilots very good salaries. Carriers like Delta, American Airlines and United Airlines pay their long haul Captains up to $350,000 a year when you take into account allowances and bonuses. Regional pilots just starting off their career will typically earn a salary of $20,000 – $40,000 a year. Pilots normally start out flying at regional carriers before moving across to major airlines where they fly bigger aircraft and earn more money. However, not all pilots go on to achieve this.

UK & Europe Airline Pilot Salary

In the UK and Europe, senior long-haul Captains flying at airlines like Lufthansa, Swiss Air, Virgin Atlantic, Iberia & KLM can be expected to earn between £150,000 – £250,000 a year. This varies depending on length of service, training qualifications, as well as bonuses, allowances and flight pay. First Officers at short haul low cost airlines can expect to earn between about £40,000 to £80,000 a year (although cadet pilots may start on less) whilst a short haul Captain pay can be between £90,000 and £150,000 a year. Some Regional or small low cost airline First Officers might start on as little as £20,000 a year for the first few years of their career, with Captains potentially earning between £40,000 – 80,000.

Asia Commercial Pilot Pay

In countries across Asia, such as China, airline pilots were in significant demand before the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, some companies were offering pilots a salary as high as $500,000 a year for experienced long haul Captains. First Officer pay can also extend upwards of $100,000 a year. Whether these huge salaries continue to be offered as world travel demand starts to recover is yet to be seen. The average salary for a commercial pilot in India is around ₹4,687,90o, with Captains earning up to ₹6,610,000 a year.

Commercial Pilot Salary Breakdown…

Commercial pilots are typically paid a base salary which makes up the majority of their pay. They are then usually given allowances for overnight stays to cover expenses as well as earning flight pay for every flight they operate. Some airlines also pay the pilot for every hour they are away from their home base. For example, if you fly from Frankfurt to Las Vegas, you will be paid for every hour from when you arrive at Frankfurt to start your duty, to when you return to Frankfurt after completing the return flight. This can be quite lucrative if it is an extended long-haul trip that goes on for 7 days. Many airlines also pay bonuses to their pilots if the company is profitable.

Commercial Pilot Pension…

Airline pilot pensions tend to be quite generous with airlines often paying an extra 15-25% of your salary into your pension. Airlines used to offer final salary pensions but this is now less common due to the high cost to the company.

Top Level Captain Pay – it doesn’t come quick!

Whilst the pay for Long Haul Captains at major & legacy airlines is a large sum, it can take many years to be promoted to such a position. Regional, low cost and short haul generally steadily lose pilots to the major & legacy airlines due to the lure of bigger pay checks and bigger aircraft. Once at a major carrier, pilots don’t tend to leave until they retire. With little in the way of company expansion, Captain positions only become available when another pilot retires. This is referred to in the industry as ‘dead mans shoes’. Promotion is based on seniority so it doesn’t matter if you are the best pilot in the airline; you will only be promoted from co-pilot to pilot (First Officer to Captain) when there is a gap to fill and this can take as long as ten to twenty years. Given that most pilots will have had to have completed a few years at smaller regional carriers before joining a major, they might not hit the top pay scales until well into their fifties.

If you enjoyed reading this article, check out our page which describes a typical day for a long haul pilot.

Check out our YouTube video on how much commercial pilots get paid…

Do I Need to be Good at Maths to be a Pilot?

Do I need to be good at Maths to be a pilot?

You need to be reasonably good at Maths in order to be an airline pilot, but you don’t need to excel at it. Being able to complete mental arithmetic quite quickly is important as you are often required to make relatively easy calculations in your head whilst flying.

The most commonly used mental arithmetic calculations are simple addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. If you are good at these types of calculations, you can quickly work out things like how much fuel you need for a flight or are burning an hour, speed distance and time calculations, and the rate of climb or descent needed.

To get an Air Transport Pilots Licence (ATPL), you need to pass a number of theory examinations. Some of these exams, like General Navigation, requires you to understand and apply Maths concepts like Trigonometry and Pythagoras theorem. However, in reality you don’t tend to make calculations relating to these concepts on a daily basis when flying a commercial jet.

What grade do I need in Maths?

Essentially, if you have achieved a good grade in Maths at GCSE level or the Secondary/High School examinations, you should be fine. If you haven’t achieved this then don’t worry, it takes some people a bit longer to grasp Maths and you may find that you get much better at it as you get a bit older. Most airlines and flight schools will want to see that you achieved an equivalent of grade C or level 4 or above in Maths, but if you get good A-Level grades or a University degree, then your GCSE / Secondary grades become less important.

The single most used calculation applied to every flight is the application of the 3 times table to calculate, using a rule of thumb, if you are too high or low when descending. This is simple calculation of removing the last three digits of the altitude and multiplying the remaining number by 3, to calculate roughly how many miles you need to descent. For example, at 30,000 feet, you would multiply 30 by 3 which gives 90. This means at 30,000ft, you need roughly ninety nautical miles to descend, assuming a constant 3-degree glide path. You don’t have time to use a calculator to work these calculations out, so you need to be able to do them quickly in your head.

Flight School & Airline Entrance Exams

Many flight schools and some airlines require you to complete a Maths test as part of the selection process. These tend to be mental arithmetic based tests where you can’t use a calculator.

Examples of Pilot Maths Calculations

Examples of the type of calculations you have to make when piloting a commercial aircraft include:

- If Air Traffic Control tell you to descent from 20,000ft to 14,000ft and reach that level within 3 minutes, what is the minimum rate of descent you require? The actual calculation is quite easy, it’s just knowing what to do with the information. All you are doing is taking the total altitude you need to lose (which is 6,000ft) and dividing it by 3 (the number of minutes in which you need to descend). The answer is therefore 2,000ft per minute.

- If you are climbing at an average of 1,800 feet per minute, how long will it take you to climb 9,000ft? The answer is 5 minutes (9,000 divided by 1,800).

- If you are burning 2.4 tons of fuel an hour, how much fuel will you burn in 2 hours and 30 minutes? The answer is 6 tons. (2.4 multiplied by 2.5).

- If you are flying at an average speed of 240kts, how long will it take you to fly 720 nautical miles? The answer is 3 hours (720 divided by 240).

- If you take-off at 16:15 and landed at 19:48, how long was the flight? The answer is 3 hours and 33 minutes.

How to Become an easyJet Pilot

How to Become an easyJet Pilot

easyJet has traditionally recruited pilots through their ‘Generation easyJet’ cadet program and also accept applications from experienced pilots.

Generation easyJet

If you don’t have any flying experience but would like to become an easyJet pilot, then applying to their pilot cadet program which they call ‘Generation easyJet’ is your best bet. If you are invited to join their cadet pilot program, you will complete your flight training with their partner call CAE. During the training you will obtain the licences required to become an A320 First Officer with easyJet.

Cadet pilots are typically required to finance their flight training through CAE themselves, although on a limited number of occasions easyJet has provided financial assistance to some pilots who were unable to fund it themselves through the ‘Amy Johnson’ initiative.

Direct Entry Pilot

If you were unable to enrol on the Generation easyJet cadet pilot program, then you may still have the opportunity to join easyJet as a pilot in the future. You can complete your flight training and gain experience at another airline before applying to join easyJet as a direct entry First Officer. In the past, easyJet have also recruited direct entry Captains.

Outlook

The pandemic has made the recruitment outlook for many airlines uncertain. When easyJet start recruiting pilots again, we will post it on our Cadet Pilot Program page.

Becoming an easyJet Pilot FAQs

How long does it take to train as an easyJet pilot?

If you join the Generation easyJet cadet pilot program, it normally takes between about 18-24 months to complete your flight training.

How much do easyJet pilots get paid?

First Officers with easyJet can expect to earn between about £50,000 – £70,000 a year.

easyJet Captains can expect to earn between about £120,000 – £150,0000 a year.

What aircraft to easyJet fly?

easyJet operate the A320 aircraft across a short-haul network around Europe.

Integrated vs Modular Flight Training

Integrated vs Modular Flight Training – Which is Better?

There are distinct differences between integrated and modular flight training routes but neither flight training footprint is necessarily better than the other. Deciding on which method of training to complete very much depends on your own personal circumstances.

As a general overview, integrated flight training is more expenses but takes a shorter amount of time making it more intensive which appeals to the airline.

On the other hand, modular flight training is normally substantially cheaper, may take more time to complete and offers much greater flexibility as to how and when you complete your training.

Integrated Flight Training Overview

Integrated training basically means you carry out all of your commercial pilot training on a full-time course at an approved flight school. It takes you from having zero hours flying time to holding a frozen ATPL in around 14-18 months. The training is intensive requiring complete commitment from start to finish.

Although the course is designed for zero-hour flight time students, it does not preclude those with previous flying experience from applying. In fact, a few hours of previous instruction may be beneficial. Many students enrol on an integrated flight training course having already obtained their PPL.

In the UK integrated training is specifically approved and regulated by the CAA and in Europe by EASA. There used to be the three “big” flight schools that offer this type of flight training; Oxford Aviation Academy (OAA), Flight Training Europe Jerez (FTEJerez), and L3 Aviation Academy, however in recent years, this list has grown into a more comprehensive list of training providers.

All the integrated schools require that you pass a selection process involving aptitude testing, Maths and English tests, group exercises and a competency interview.

What Airlines Want…

Many airlines say they prefer graduates from integrated flight school. They suggested that if you can keep up with the fast-paced training and very steep learning curve associated with integrated training then the airline can be fairly confident that you will not have any problems with the subsequent type rating and line training.

Some airlines only recruit low hour cadets from the four CAA approved integrated schools. Airlines such as Virgin Atlantic, easyJet, TUI, Emirates and Qatar Airways all run mentored courses though such courses.

Integrated training is geared up to prepare you for a job as a commercial airline pilot from day one. You are required to wear uniform, and taught to operate the aircraft in a similar manner (as far as practicable) to that of a commercial airliner.

The training is well structured and the standard is regarded as very high. The structure of the courses varies from school to school but all culminate of taught ground school theory subjects, single engine elementary flight training before moving onto the more advanced instrument flight rules training on the multi-engine.

What Flight Training School is Right for You?

The best way to choose which school is right for you is to go and visit them. Each offers a different training environment and facilities, and the layout of the syllabus tend to have some differences. For example, at Flight Training Europe (FTEJerez) the students have their accommodation and catering on campus. This can be very useful in terms of practicality and convenience. Not having to worry about cooking dinner after a long day of ground school, or not hanging around flight operations all day having to wait for the weather to clear up are very handy commodities.

You also have benefits of an onsite swimming pool and bar making relaxing on your days off pretty easy. Others may find this to be a bit claustrophobic as during the fourteen months of training you get very little time off and so much time living and working in one place, especially abroad, can be daunting.

Integrated Flight Training Advantages

- Some airlines recruit directly from integrated flight training organisations. For example, easyJet recruit directly from OAA and L3 Aviation Academy.

- After completing training, you are often placed in a holding pool until an airline recruits you.

- It’s an intensive course which the airlines like as it demonstrates you can cope with a steep learning curve.

- All of the training is done with one flight training organisation. This means an accurate record can be kept of your flight training performance, something which the airlines value.

- Integrated flight training organisations must be approved by the state regulator. This pretty much guarantees a high standard of pilot training.

- The quality and consistency of the flight training is often better.

- You will probably get your ATPL(f) licence quicker.

- It takes from you zero flying experience to having the licences needed to pilot a commercial aircraft as a First Officer.

- There are potentially additional accreditations that might be available through an integrated flight training course, such as bolt on aviation degrees allowing you to obtain a BSc at the same time.

- Flight schools often provide support to their graduates until they secure a job with an airline. Some schools will offer assessment preparation sessions and practice simulator assessments.

- Some flight schools have performance guarantee schemes due to the faith in their selection process. This means if you didn’t reach the required standard to gain various licences, you could get your money back.

Integrated Flight Training Disadvantages

- Usually it’s much more expensive than the modular pilot training route.

- You complete the training to a strict timetable i.e. less flexibility.

- In reality, you are unable to work in any other role whilst on the course so you would need the money or loan to finance the course upfront.

- There is more risk in the sense of if there was a significant global event that affected airline recruitment (like the Covid-19 pandemic), you will be committed to continue with your training even if the immediate job prospects looked bleak.

- You can’t pay as you go in the traditional sense. Rather you pay some upfront and then in installments during the flight training.

- The finances required to pay for the pilot training can be difficult or impossible for some people to secure.

If you are interested in Integrated Flight Training, you can check out our specific Integrated Flight Training Organisation List. This will help you decide which pilot training school is right for you.

Modular Flight Training Overview

Modular flight training is traditionally cheaper than integrated. You can choose where and when you complete your training which gives you the benefit of being able to budget appropriately, paying for you training as you go, rather than spending a large upfront sum that is required for integrated courses. You can do it as quickly or slowly as you like, which gives you the opportunity to work while getting your various licences.

The hour building required for the Commercial Pilots Licence (CPL) issue can be completed in other countries, with many people choosing to do this in the United States because of the cheaper cost of flying.

The typical route for modular training is as follows:

- Private Pilots Licence (PPL)

- Hour Building

- Airline Transport Pilot Licence (ATPL) Theoretical Examinations

- Commercial Pilots Licence (CPL)

- Instrument Rating (IR)

- Multi Crew Cooperation Course (MCC)

So why doesn’t everyone go through the modular route if it’s cheaper?

- Historically, many airlines have preferred integrated students because of the quality and intensity of the training on such a course. This can’t be guaranteed through the modular route.

- No links with airlines. Most integrated schools have links with airlines, allowing the schools to recommend students to a specific airline when they perform to a high standard.

Modular Flight Training Advantages

- It can be much cheaper than an integrated course.

- You can complete it in your own time alongside full or part time employment.

- You can train at your own pace.

- Less risk in that if there is a substantial downturn which affects the airlines, you can stop the training and continue at a later date

- You aren’t committed to work for a particular company, which might be useful if lots of airlines are recruiting when you complete your training – you can be a bit fussier about who you apply to.

Modular Flight Training Disadvantages

- It takes longer to complete.

- It can be difficult to maintain consistency through having different instructors at different schools.

- The training emphasis isn’t always on becoming an airline pilot and therefore the training can be less focussed on the end result.

- Generally speaking, modular flight training organisations tend not to have employment ties with commercial airlines.

- Arguably, it requires more discipline as there is more emphasis on self study.

- Many integrated schools recognise they are treating airline pilots from day one, this might not be the case at modular flight schools.

- Historically it has been harder to modular students to secure employment compared to integrated students. Modular students to get jobs, but it’s probably a bit harder to do so as you can’t benefit from the airline ties of a big flight training organisation.

Mentored Airline Cadetship

The majority of airline run pilot training schemes are known as “mentored” programs. The airline selects its cadets to enroll them onto an integrated flight training course where their progress throughout the course is monitored and evaluated by both airline and flight school alike.

The airline will expect a high standard to be met, and subject to this being achieved, the cadets are usually taken on by the airline at the end of their training. Despite being sent to carry out the flight training on behalf of airline, a cadet pilot course requires an outlay of around £100,000 and the onus to secure such finances lays with the student not the airline.

The Risks Associated with Flight Training

Up until the global economic downturn in 2008, if like most people, you didn’t have a spare eighty thousand pounds sitting in your bank account, the finances could be acquired though an unsecured loan from several different banks.

Unfortunately banks now require security for such a loan in the form of an asset(s) such as property. For many people who are looking to commence their training, such assets are not easily, if at all accessible.

This has made the industry somewhat elitist, as it precludes those from a less privileged background from obtaining the resources to commence the training. Some people are fortunate enough to have parents that may be willing to provide security for the loan in terms of the family home, but this in itself is a hugely risky commitment.

Finance

If you were to fail to secure a job after completing training and furthermore, (you or the guarantor) were not in employment which would ensure loan repayments of between £700 – £1200 a month for around ten years, the security placed on the loan may be repossessed. This has happened in the past and will continue to occur in the future, and this is why it is vital to have a backup plan before making such a huge commitment.

Even if the finances are in place, you must think long and hard about the prospect of parting with £100,000 to chase a dream that may never happen. This is quite a sobering prospect, but there are people who take the “it won’t happen to me” attitude, only to be left crippled with debt. The fact is that there are more fATPL holders than commercial pilot jobs, and as such there is always a risk that one will never achieve their goal of sitting in the right hand seat of a commercial jet.

Before committing to your commercial flight training, we strongly recommend you have a read of our “Employment Prospects After Flight Training” article.

Integrated Flight Training Organisations

Integrated Flight Training Organisation Directory

If you’ve decided to go down the integrated flight training route, rather than modular, as a “White Tail” (not mentored or sponsored by a specific airline), choosing which flight schools is best for you can be a tough call. We’d recommend visiting and talking to the various flight schools to see which best suits you.

Integrated flight schools, which are EASA/CAA regulated ‘Approved Training Organisations’ (ATOs), have the advantage of having close links with airlines, which can lead to a job on completion of training. Airlines which offer cadet pilot mentored programs will typically place their cadets on one of these integrated courses. We would recommend applying for an airline mentored place at one of these integrated flight schools before applying as a “White Tail” as this will provide the most secure way into the industry. The latest cadet pilot programs can be found here.

Whilst the flight schools provide a set course price, the establishments tend to differ with what’s included in this price. For example some include accommodation, whilst others don’t. It is important to take such variables into account when considering which is the best option for you.

Flight School Entry Requirements

The typical criteria to be eligible to apply to an integrated flight training program within Europe is as follows:

- Be 17 years old or greater

- Hold a valid Class One medical

- Be fluent in English language (written and spoken)

- Have a secondary school education or greater with 5 grades A-C

- Have the right to live and work in the EU

But this will differ between each organisation.

Integrated Flight School Checklist

We’ve written out a checklist to help you choose the flight training organisation. Before you make your decision on which flight school to attend, we’d recommend you consider the following:

- What is the total price?

- What does the total price include? Equipment, uniform etc…

- Are the payments made in instalments? Be very careful about paying for the full cost of your training upfront. If the training school goes out of business half way through your training, you will have a very difficult time trying to recover the money. Most integrated flight training schools will allow you to pay monthly instalments as you progress.

- What happens if you require any additional training? What is the cost of this?

- Does the price include any exam / flight test retakes?

- How long does the course take?

- What happens if it takes longer because of bad weather or other unforeseen issues? Who is responsible for additional accommodation costs etc?

- Where does the training occur (training is often split between countries due to reduced cost of aircraft rental / landing fees / good weather etc…)

- Is accommodation included throughout the various stages of training?

- If accommodation isn’t included, do they support you in finding suitable accommodation?

- What ties does the school have with airlines?

- What is the school’s placement record with airlines like? Can they provide any statistics?

- What do current students think about the training they are receiving?

- Do they offer support in seeking employment after obtaining your licences?

- Is an airline assessment preparation day included in the course? This is something many flight schools now offer.

Integrated Flight School Directory

Airline Pilot Academy (APA)

Updated: January 2021

Duration: Approximately 17 months

Price: £86,565 (including accommodation and transport costs)

Location: Bournemouth, Florida, Utrecht

Airways Aviation

Updated: January 2021

Duration: Approximately 71 weeks

Price: €95,000 excluding accomodation

Location: Montpellier, France

Baltic Aviation Academy (BAA)

Updated: January 2021

Duration: Approx 2 years

Price: Price on application

Location: Lithuania

Notes: Accommodation not included

CAE Oxford Aviation Academy (OAA)

Updated: January 2021

Duration: Approximately 24 months

Price: £90,000 excluding accommodation

Location: Oxford, UK & Arizona, US

L3 Aviation Academy

Updated: January 2021

Duration: 18 to 24 months

Location: United Kingdom or Portugal

Price: £86,000 excluding living expenses

European Flight Training (EFT)

Updated: January 2021

Duration: 12 – 15 months

Price: Price on application. Accommodation included.

Location: Florida, USA

Flying Time Aviation (FTA)

Updated: January 2021

Duration: Not stated (previouslly 16 months)

Price: £87,950

Location: Brighton, UK and Teruel, Spain

FTEJerez

Updated: January 2021

Duration: 62 weeks

Price: €119,500 – Accommodation and full board included

Location: Jerez, Spain

QUALITY FLY

Updated: November 2023

Duration: 78 weeks

Price: €67,750.00 – Accommodation available at €550.00 a month

Location: Madrid, Spain

Stapleford Flight Training – Jetway Integrated

Updated: January 2021

Duration: Not specified

Price: £74,995 – Accommodation not included

Location: Stapleford, UK

Is there a Pilot Shortage?

Is There a Pilot Shortage?

Prior to Covid-19, the answer was yes there was a global pilot shortage but the situation was a bit more complex than the straight forward answer might suggest. However, at present in 2021, there is no pilot shortage due to the impact on aviation of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Whenever you hear reports of ‘pilot shortage’ it is usually referring to a world-wide shortage, not necessarily a shortage in Europe or the UK. The shortage is always specific to a region, type of operation and pilot experience.

Covid-19 Pandemic & Aviation

The impact on of the Covid-19 pandemic on commercial aviation has been catastrophic. With huge portions of fleets being grounded for almost a year, tens of thousands of pilots around the world have found themselves out of work. IATA do not anticipate airlines recovering to pre-Covid levels of operation until 2024 and beyond.

However, flight training provider CAE have stated that due to natural attrition (such as retirements), the world will require 260,000 pilots over the next 10 years. This suggests that whilst the immediate outlook is bleak, when the industry recovers, employment opportunities will start to open up.

Pilot Shortage Pre-Covid

The remainder of this article was first published prior to the Covid-19 pandemic but address the age-old questions that come up when this topic is discussed.

First of all, let’s get the statistics out the way. In 2016, Boeing have forecast that the aviation industry will require 679,000 new pilots between now and 2035. Airbus have said that between 2016 and 2035, there will be a requirement for in excess of 500,000 new pilots. Keep in mind though, that this is a worldwide forecast.

Flight Schools

It’s a general point, and I don’t want to tarnish all flight schools with the same brush, but if you are considering starting your flight training, be aware that lots of Flight Training Schools will always tell you there is a looming pilot shortage regardless of the market state. To them, ultimately you are profit, and to make profit, they need people to train with them. It’s not going to be good for business if they tell prospective students that there is no point training as there are no jobs! It’s not the case at the moment, as the market for freshly graduated low hour pilots is better than it’s been in a long time, but keep it in mind.

Airlines

Secondly, the airlines want to avoid a pilot shortage from occurring, in fact they want the exact opposite; lots of pilots on the job market. It’s simple economics. Pilots cost a lot of money to airlines. They get paid a lot and have lower productivity than other personal due to flight time limitations. If you have lots of unemployed pilots, it puts a downwards pressure on wages as you have lots of applicants for one position. The opposite occurs when there’s a shortage; airlines have to put up terms and conditions to attract the best candidates. Lots of pilots looking for employment suits airlines.

Terms and Conditions

In 2008, we saw a recession across Europe and other parts of the world. This put a lot of airlines out of business and left a lot of pilots unemployed. As a result, the last 10 years have seen pilot wages stagnate in many regions as pilot supply has outstripped demand. This pressure on terms and conditions wasn’t helped by an increase in the retirement age in Europe from 60 to 65 being introduced. This meant that pilot who were planning to retire, could stay on for an additional five years if they wanted to.

More recently, airlines have again been expanding, and the major carriers have been recruiting heavily. When the major carriers recruit, it tends to shake up the employment market as people move up the next step of the ladder. As a result, there are less pilots to choose from and we are now slowly starting to see terms and conditions improve at mainly airlines, as they look to generate interest from the most capable crews.

Airline Finances

As airline financial performance has started to improve, their pilots have started to demand a share in the profit through increased wages. Lufthansa pilots have been striking throughout 2016 to fight for a better increase in their salaries as they haven’t had a pay rise since 2012. Delta Airlines pilots recently secured a whopping 30% increase in their pay.

Middle East & Asia

The pilot shortage is more notable across the Middle East and Asia. Airlines in this part of the world are expanding rapidly and don’t have enough established and experienced local pilots to fill the seats. Therefore, they need to recruit pilots from parts of the world where aviation has been established for a longer period, such as Europe, America and Australasia. They are offering huge sums of money to attract crew, in some cases in excess of $20,000 a month.

However, whilst there is clearly a pilot shortage in these parts of the world, it isn’t for inexperienced cadet pilots straight out of flight school, it’s for experienced First Officers and Captains. An experienced Captain takes years to train and build up the required experience whereas a cadet pilot can be ‘on the line’ in as little as 18 months.

Who does the pilot shortage affect first?

In general, a pilot shortage would usually hit the regional carriers first, as they are unable to offer the terms and conditions found at the charter, low cost and legacy airlines.

Naturally, most people aspire to improve their living standards throughout their career, and this means moving up the ladder to the next job. Once working for a legacy carrier, there isn’t a step up, and therefore pilot retention at these companies is very high and generally only recruit when they expand and to replace retired or medically unfit crews.

Regional Airlines in the United States

The pilot shortage is particularly notable at regional airlines in the United States. In the US, the FAA introduced a requirement for pilots to have 1500 hours total flight time before operating for a commercial transport operator. You graduate from flight school with around 250 hours, but you now need to build those hours up through instruction, banner towing, general aviation etc. The regional carriers have traditionally recruited the cadet level entry pilots, and this has significantly stemmed the flow of available candidates.

Europe

The European market is currently doing pretty well with recruitment for pilots of all experience levels from legacy carriers through to the regional operators. It’s debatable whether you could call it a shortage, rather than just a good employee’s market for the moment. Flybe did however suggest last month that a shortage of pilots was holding back growth.

To assess if or how bad any pilot shortage in Europe will get, you need to look at potential expansion opportunities and how saturated the market currently is. Much of Europe is well connected to Europe and millions of people now have access to air transport thanks to the success of low-cost carriers over the past ten years.

Can there be more expansion?

How much more room is there for airlines to expand in order to offer services to new destinations and untapped markets? That’s yet to be seen but it’s certainly nothing like those opportunities in developing counties with huge populations like India and China. That being said, some airlines like have impressive numbers of aircraft on order, and many of these frames are for expansion rather than fleet replacement.

Conclusion

Looking at it independently, now is a good a time as any to start your flight training. You must however, consider this. Just because you have a licence, you don’t have the right to secure employment as a professional pilot. The airlines want more than just a licence, they need a competent commercially minded operator and a frozen ATPL doesn’t guarantee this. Just because there is a job opening, meeting the minimum requirements doesn’t mean you’ll get it, even if you’re the only applicant. Yes, there is a pilot shortage across many parts of the world but this isn’t a job guarantee.

Choose your training route and flight school carefully, and be aware of the qualities that airlines are looking for in their pilots. It’s much more than just stick and rudder skills.

Airline Pilot Medical Requirements

What are the medical requirements to become a pilot…

To exercise the privileges of a Commercial Pilots Licence, you must be in possession of a valid Class 1 Medical certificate. This is something you should seek to obtain before you start your flight training just in case a medical condition (which on occasions people aren’t already aware of), prohibits you from being awarded a Class One Medical certification.

The requirements are not particularly stringent, and a normal healthy person should have no problem being awarded one. The medical examiners are generally concerned with if you have the ability to do the job of a commercial pilot without difficulty or impedance, such as due to reduced mobility, poor hearing or eyesight and that the potential for you to suffer from acute incapacitation (such as due to a seizure, collapse, heart attack or stroke etc.) is negligible.

Airline Pilot Medical Requirements

The very first recommendation to any aspiring pilot is to obtain a Pilot Class One Medical certificate. This is a mandatory requirement for all airline flight crew in order to operate a jet commercially. For a UK or European issued medical certificate, the initial assessment can take place with a specifically authorised CAA Aviation Medical Examiner (AME) listed on their website.

Unfortunately people invest significant amounts of money in obtaining a Private Pilot’s Licence (requiring only a class two medical), with the view to continue training towards a commercial licence. They can then find out that they were ineligible for a class one medical, and are therefore unable to pursue a commercial piloting career. So make sure you can pass the medical requirements before commencing your pilot training.

Initial Class One Pilot Medical Assessment

During the initial Class One medical assessment you are tested and checked for a general level of good health and any specific disqualifying conditions are identified. Unfortunately for some, this occasion may highlight an underlying medical condition which has not before been detected, and the medical certificate will not be issued. Some conditions are not necessarily disqualifying but may require further investigation and testing.

What’s included in a Pilot Class One Medical Assessment?

The following is assessed at the initial examination:

Disclaimer: The information below has been taken from the UK CAA website. We have provided the information for use as a guide only. Any medical enquiries should be directed to the regulatory authority for your country. This guidance was correct at the time of posting but may since have changed. The list is non-exhaustive.

- Medical history review

- Eyesight test – “If you wear glasses or contact lenses it is important to take your last optician’s report along to the examination. An applicant may be assessed as fit with hypermetropia not exceeding +5.0 dioptres, myopia not exceeding -6.0 dioptres, astigmatism not exceeding 2.0 dioptres, and anisometropia not exceeding 2.0 dioptres, provided that optimal correction has been considered and no significant pathology is demonstrated. Monocular visual acuities should be 6/6 or better.”

- Hearing test – “Applicants may not have a hearing loss of more than 35dB at any of the frequencies 500Hz, 1000Hz or 2000Hz, or more than 50dB at 3000Hz, in either ear separately.”

- Physical Examination – “A general check that all is functioning correctly. It will cover lungs, heart, blood pressure, stomach, limbs and nervous system.”

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) – “This measures the electrical impulses passing through your heart. It can show disorders of the heart rhythm or of the conduction of the impulses, and sometimes it can show a lack of blood supplying the heart muscle. Changes on an ECG require further investigation. A report from a cardiologist and further tests (for example an exercise ECG) may need to be done.”

- Lung function test (spirometry) – “This tests your ability to expel air rapidly from your lungs. Abnormal lung function or respiratory problems, e.g. asthma will require reports by a specialist in respiratory disease (UK CAA Asthma guidance and Guidance for Respiratory Reports).”

- Haemoglobin blood test – “This is a finger prick blood test which measures the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood. A low haemoglobin is called anaemia and will need further investigation.”

- Urine test – “You will be asked to provide a sample of urine, so remember to attend for examination with a full bladder. This tests for sugar (diabetes), protein or blood in the urine.”

All content in the quotation marks has been referenced from the UK CAA medical website.

How strict is the Class One Medical examination it?

The award of Class One Medical certifications seems to be more lenient as science and studies have evolved. For example, it is now permissible to hold a Class One Medical if you have either Type 1 or 2 diabetes as long as you demonstrate you can effectively manage your blood sugar levels. If there are any doubts as to your fitness to hold a medical, you may be required to demonstrate your competency in the simulator (for example a practical hearing observation).

Operational Multi-Crew Limitation (OML)

Some conditions (such as diabetes), whilst not immediately disqualifying, my require a restriction to be placed on your authority to operate a commercial aircraft. This is referred to as an Operational Multi-crew Limitation or OML. This allows you to exercise your class one medical privileges only as part of a multi-crew environment. Crew who have an OML restriction may not fly together as part of a 2 crew flight, and an OML holder may not fly with another pilot over the age of 60.

Pilot Medical Renewal

After the medical initial issue, you are required to attend a medical assessment on an annual basis until the age of 60, then every six months until you reach 65 which is the age at which class one medical privileges are revoked.

Items such as ECG and audiograms are retested at periodic intervals, increasing in frequency with age. For example, ECGs are carried out every 2 years between the ages of 30-39 then yearly until 59, then every 6 months until retirement.

What if I Can’t Get a Pilot Class One Medical?

For those unlucky enough not to be able to obtain a class one medical, you may still be able to hold a class two medical which allows you to operate light aircraft with a private pilot’s licence (PPL). A class two medical is effectively a less stringent class one medical, with test renewals initially taking place every two years.

Pilot Medical Revoked

A commercial pilot is reliant on maintaining his or her class one medical in order to exercise their flying privileges. The regulatory authority may revoke the medical at any time, consequently grounding the pilot either temporarily or permanently. Some pilots find themselves in a position where there medical is revoked due to a medical condition occurring.

With continual developments in scientific knowledge and medical treatment, coupled with the regulatory authorities occasionally reviewing the disqualifying conditions, some people have managed to get back into flying commercially after fearing their career was over due to a lost medical.

What may have previously been a disqualifying condition, is now often assessed on an individual basis.

It’s worth considering having some additional loss of income insurance (or loss of medical insurance) in place to ensure you are financially secure if you do lose your medical. Trying to find another job which offers a similar level of remuneration as a pilot’s salary is not easy.

How to Finance Commercial Flight Training

How do I pay for my commercial flight training?

There are a number of ways to pay for your commercial flight training. To fund or finance your airline pilot training, you generally have the following options:

- Be accepted for a large bank loan, secured against a property to pay for your integrated flight training.

- Be accepted for an airline specific cadet program where the airline either sponsors your training or will act as a guarantor for a loan to fund the training.

- Complete flight training through the modular route to allow you to continue working and pay for your flight training as you go / can afford it.

- Save up for a number of years whilst in full time employment before self-funding an integrated flight training course.

- Become a pilot with the military who pay for your flight training, then convert your licences to a civil commercial licence when you’ve finished your minimum service requirements.

Affordability

Unfortunately for a lot of people, financing the flight training is the biggest obstacle to becoming a commercial airline pilot. With the cost of integrated flight training for airline specific cadet programs now exceeding £120,000 / €140,000, securing the funds needed to finance the training can be both very challenging and daunting.

Bank Loan

With integrated flight training programs starting at about £80,000, there are only a handful of realistic options you can use to fund the training and one of these is a bank loan. Due to the amount of money you will need to borrow, banks will require a ‘guarantor’. This means the loan is secured against an asset, and the asset is typically a property.

The majority of prospective commercial pilots want to start their flight training shortly after leaving school and clearly you are unlikely to own a property at his age. Therefore people are generally reliant on their parents or other family members (such as grandparents) securing the loan against their property for you or re-mortgaging the house.

Unfortunately this is not an option for everyone as not all families own their home or have paid off enough equity in the mortgage.

Some banks offer flight training specific loans which offer payment holidays until you’ve finished the training. Others, you need to start paying the loan back straight away but clearly you won’t be earning any money whilst you are completing a full time integrated commercial flight training course.

The Risk of a bank loan

This option does not come without risk. If you don’t end up getting a flying job as soon as you’ve completed your flight training, can the loan repayments still be made? Thousands of people have had their airlines cancel their provisional offer of a job half way through their training or have even been made redundant from their airline whilst still trying to pay off the loan. You need to think about what your contingency plans are if it worst happens to protect the property you may have secured the loan on.

Although you’d hope never to need it, this is where having some additional qualifications or previous work experience to fall back on can be a invaluable.

Cadet Programs / Sponsorship

Since the tragic events of 11th September 2001 in New York City, very few airlines around the world have continued to offer flight training sponsorship. Just prior to the Covid-19 pandemic there were signs this was starting to change. For example, in 2019 Aer Lingus opened their Future Pilot Program where the selected cadets were fully funded.

British Airways, Virgin Atlantic and easyJet were prepared to act as a guarantor for loans for cadets who were successfully accepted onto their pilot programs. Some airlines such as Emirates were prepared to pay for their cadets flight training in full although this was only applicable to UAE nationals.

Airlines have felt the full financial strain of the Covid-19 pandemic and it will likely take many years to recover and perhaps even longer to pay back the loans they needed and build up a healthy balance sheet. With many thousands of pilots currently unemployed, it would seem unlikely that any fully sponsored or loan guaranteed schemes are likely to return any time soon.

Complete Modular Flight Training

The beauty of modular flight training is that you can complete each bit of training as when you choose to. Basically you dictate the time table. It’s also a much cheaper way of getting your commercial pilots licence. Doing it this way allows you to keep working whilst completing your flight training on the side, for a cheaper price, and when you can afford it.

You can complete modular flight training for between £/€ 35,000 – £/€ 50,000. Whilst this might seem like a lot, it’s still significantly cheaper than integrated flight training and makes it more manageable. Clearly the timeline for how long it takes to complete the training will depend on how much you earn / can afford.

When completing modular flight training, you can also use smaller unsecured loans to help speed up the training, particularly the latter parts if needed.

After reading this, you might wonder why anyone completes integrated flight training; there are clear advantages and disadvantages for both.

Save Up

If you’ve got your heart set on an integrated flight training program and can’t use a loan to fully fund it, starting on another career path and saving up over a long period can work. It seems daunting but if you start a different career at the age of eighteen and manage to save £/€10,000 a year you can start your commercial flight training at the age of twenty eight and potentially have joined an airline by the age of thirty. It will take a huge amount of perseverance and motivation but airline recruiters are very impressed with people who have shown such determination to pursue their dream job.

Military Route

If you join the military as a pilot, they will pay for all your flight training and you can convert your flying experience into a commercial pilots licence when you leave. However, we would not recommend you apply to the military purely because you want to be a commercial pilot – you really need genuine motivation to become a military pilot with a full appreciation of the role and lifestyle. Ultimately you could be sent to war or be stationed all over the world.

Manually flying fast jets or heavy transport aircraft at low level is some of the ‘real flying’ you won’t experience with a commercial airline. Doing this for a number of years (be aware of the minimum service requirements) prior to transitioning to the commercial world is the ideal route for some people.

BBVA Secured Bank Loan Example

A Spanish bank called BBVA offers specific flight training loans. The key points (taken from the BBVA website) are as follows:

- Maximum amount: Full cost of the course plus living expenses if required.

- Minimum amount: £45,000

- Repayment period: Up to 10 years.

- Payment holiday: Up to 24 months. Interest will still be charged during this period

and will be added to the loan balance. - For up to 24 months after your payment holiday, your monthly repayments can be

reduced by 25%. Interest will be charged on the unpaid monthly repayment amount

and will be added to the loan balance. - Security will be required: We will require a first or second ranking charge or

mortgage over a property located in the UK to secure your loan. The maximum amount

we will lend is 60% of the value of the property (whether for a first or second ranking

charge). We do not offer unsecured lending for pilot training loans. - Interest: Bank of England Base Rate (variable) plus 2.5% per annum.